Scientific Name

Chilabothrus chrysogaster

Described and named by Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), a paleontologist and zoologist of great stature. He worked at the Smithsonian, the British Museum, Jardin des Plantes and became the Curator of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

[intergeo id=”QO2ATM”][/intergeo]

Holotype

Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia (ANSP): No. 10322. Collected by Professor Adrian J. Ebell. The present whereabouts of the holotype is unknown.

Type Locality

“Turks Island”, possibly meaning Grand Turk Island or Turk Islands. Previous to 2010 no other specimens had since been recorded from the Turks Bank . In 2010 four individuals were found on Gibbs Cay (Turks Bank) 1.5 km from Grand Turk .

Subspecies

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster chrysogaster

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster relicquus (Barbour & Shreve, 1935) (Epicrates relicquus Barber and Shreve, 1935, 40(5): 362). Type Locality: Sheep Cay, Bahama Islands. Holotype: Museum Comparative Zoology no. 37891. Collected by J. Greenway, 1934. Distribution: Sheep Cay and Great Inagua.

NOTE: Previously Chilabothrus chrysogaster schwartzi was a third subspecies, but has recently been elevated to the rank of full species Chilabothrus schwartzi.

Synonyms

- Homalochilus chrysogaster [558]

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster : 439

- Epicrates chysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster : 38

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster : 218 [219]

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster : 108

- Epicrates striatus chrysogaster : 131

- Epicrates striatus chrysogaster

- Epicrates striatus chrysogaster

- Epicrates striatus chrysogaster : 150

- Epicrates angulifer chrysogaster : 74

- Epicrates striatus chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster [92] [93]

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster [21]

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster [2]

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster Bulian, 1989: 27 [28] [29] [30] [31]

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster 22

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster : 19

- Epicrates chrysogaster Mattison, 1995: 89

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster : 44

- Epicrates chrysogaster Mattison, 2007: 91

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster chrysogaster : 107 [108] [109] [110]

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster

- Epicrates chrysogaster

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster : 10

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster : 282

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster : 37

- Chilabothrus chrysogaster chrysogaster Reynolds, Colosimo, Peek, Vanerelli, Bradley & Gerber, 2020: 610 [611]

The name chrysogaster refers to the coloration of the species which Cope described as: "Color, light fawn brown above, below golden yellow" From the Greek chrysos = golden and gastrum = belly.

Cope, in his 1886 "An Analytical Table of the Genera of Snakes", considered Homalochilus, Pelophilus, Dendrophilus and Piesigaster all synonyms of Chilabothrus.

Common Name

Turks and Caicos Boa.

Description and taxonomic remarks

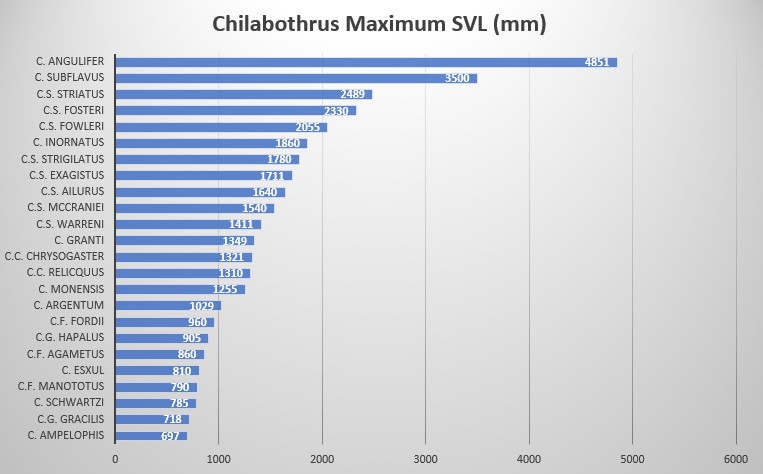

According to Chilabothrus chrysogaster chrysogaster is characterized by the following combination of characters (N = 6): low number of ventral scales (245–259), low number of ventrals plus subcaudals (320–339), low number of dorsal scale rows at midbody (39–43), modally 14 supralabials with usually 3 supralabials entering the eye, modally 15 infralabials, pre-intersupraoculars are 3, inter-supraoculars are 2, post-intersupraoculars are 3. Reynolds reports a maximum SVL of 1321 mm .

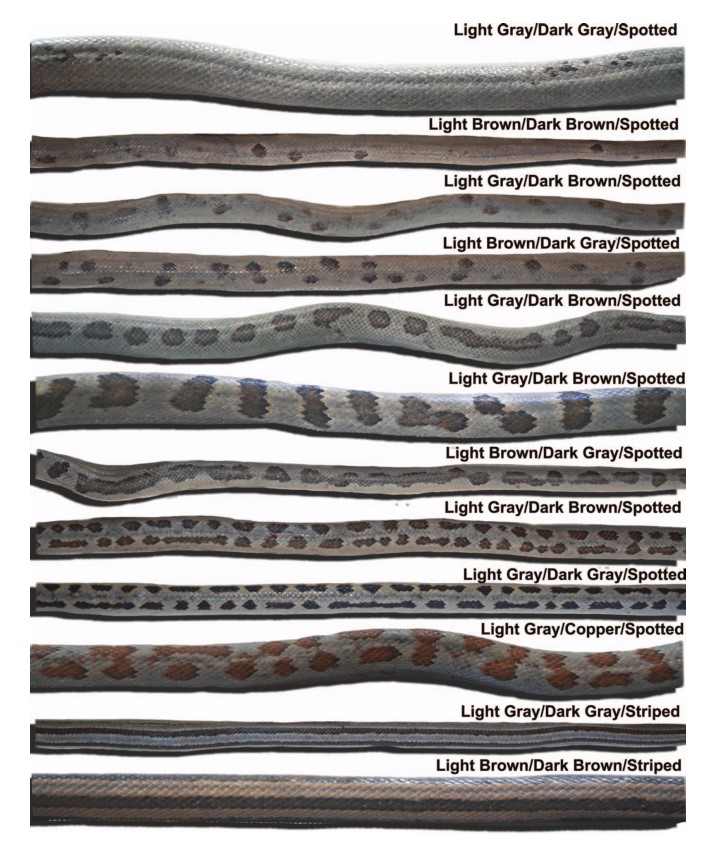

A pattern consisting of either a series of angulate to ovate dorsal blotches without a secondary lateral row, or a series of 4 longitudinal dark-gray stripes, the 2 dorsal stripes at about the level of the central portion of the position of the blotch series, and the lateral pair of stripes on the lower sides in about the position of a secondary series of lateral blotches.

* Taken from

Chilabothrus chrysogaster is the only species in the genus that has two pattern phases: a striped phase and a blotched phase. The striped phase is known to occur only in the Caicos Bank . Aside from these two very obvious phases, recent research (Reynolds etal. 2020) indicates that a larger variety of color and pattern phases exists in this species. Some animals display blotches which are boldly marked while others have small and few blotches, giving the boa the appearance of being patternless. See also .

The recently published results of a study conducted from December 2007 to March of 2018 focused on phenotypic and morphological data. The study documented ten color pattern and color morphs, with the possibility of additional colors and patterns, within the species . The only other species that exhibit this type of variation in color and pattern are C. subflavus from Jamaica, C.s. striatus from eastern Hispaniola (the so-called DRMB erythristic morph of the species) and, to a much lesser degree, C.s strigilatus from the Bahamas.

In regards to its size, Tolson and Henderson categorized these boas as a medium sized member of the genus Chilabothrus (referred to as Epicrates at the time and thus included South American Rainbow Boas) . We agree with that view as but five species exist in the genus Chilabothrus that are smaller in size and weight (Chilabothrus ampelophis, C. fordii, C. gracilis, C. granti, C. monensis). However, these snakes are by no means large. During an extensive study on Big Ambergris Cay, researchers captured a total of 237 individual snakes. The average total length was 802.8 +/- 92 mm (range = 497–1199 mm). Females were significantly larger than males in SVL but not in TL. The weight ranged from 17-390 g averaging at 97+/- 51.7 g for a sample of 187 snakes. Again, female mass was significantly higher than male mass .

A report of an unusually large specimen came from Kew, North Caicos. The animal which had been found during remodeling works and was kept in captivity for educational purposes for three years, measured 1540 mm SVL, with a mass of 1100 g, and a tail length of 228 mm. While this specimen certainly was extraordinary in size and mass, the three years of captivity and, quite possibly, excessive diet might have contributed to its dimensions. In contrast, the largest specimen found in the wild (North Caicos), an adult female measured 1321 mm SVL, 228 mm TL, mass of 525 g .Bulian raised four captive born animals. The females had after four years and three month a size of 105 cm and 115 cm respectively and a mass of 435 g and 440 g. The males of the same age measured 90 cm and 390 g and 80 cm and 190 g. At ten years of age, the single remaining female (one female died while pregnant) had a length of 123 cm and a mass of 520 g. The males were 121 cm with a mass of 500 g and 113 cm with a mass of 490 g .

Evolution

No fossils of C. chrysogaster have been found as of yet. However, subfossil remains have been found in prehistoric middens on Middle Caicos and Grand Turk Islands. Though the percentage of these remains on the total number of remains is very small, this nonetheless indicates that C. chrysogaster might have been an occasional food source for prehistoric humans .

The relationship status of the different Chilabothrus species has recently been re-evaluated. According to this new molecular phylogeny, Chilabothrus chrysogaster is closest related to C. argentum, C. schwartzi, C. exsul, C. strigilatus and C. striatus. The species has been evolutionary isolated for the last 4.1 Million years . Reynolds and so-workers discovered a very shallow genetic diversity in C. chrysogaster . This shallow genetic diversity might either indicate a very limited number of founder animals on the islands or alternatively, that previous evolutionary bottlenecks favored a particular genotype. Interestingly, despite the limited genetic diversity, a highly diverse array of coloration and pattern occur in this species . It will be highly informative for evolutionary biologists to analyze the genetic, environmental and developmental biological factors which enable and favor the maintenance of this diversity within this species despite the small gene pool.

Distribution

The subspecies occurs on at least 10 islands on the Caicos Bank and two islands on the Turks Bank. Caicos Bank: Caicos Cays, Joe Grant’s Cay, North Caicos, Middle Caicos, East Caicos, Providenciales, Dellis Cay, Parrot Cay, Big Ambergris Cay, Little Ambergris Cay. Turks Bank: East Cay , Gibbs Cay . Subfossil remains have been reported from Grand Turk .

[intergeo id=”QNwETM”][/intergeo]

The flags on the map show the type localities of both subspecies of C. chrysogaster

Habitat

Nocturnal in nature, Chilabothrus chrysogaster is frequently found hiding under lime stones during the day and actively foraging at night. Found inside of a log in Cocos grove on Great Inagua . Can be found in diurnal refugia such as logs, limestone rocks, near water cisterns, subterranean interstices, human debris, palm litter, dumps and gardens .

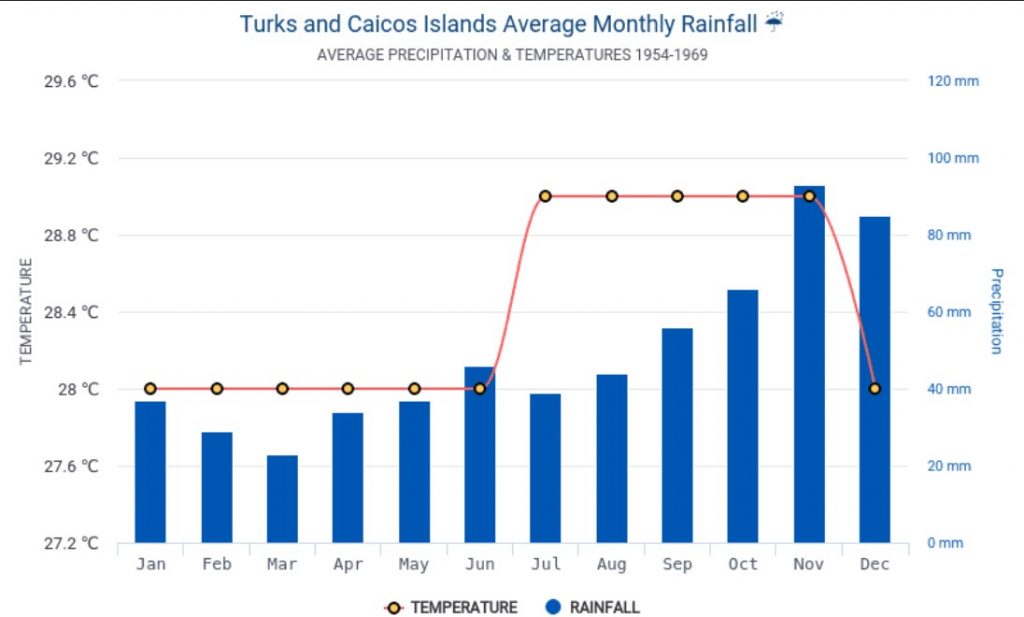

On Big Ambergris Cay the average estimated surface area of the rocks under which boas were taken was 1562 cm2, with a range of 500–3248 cm2, the largest being toward the upper limit of hand-movable rocks. Average soil temperature under the rocks was 27.58°C, 1.88°C less than the average ambient air temperature at the time of capture . Unfortunately, the researchers didn’t measure the humidity under the rocks as compared to the humidity in the ambient surroundings.

Since the Turks and Caicos Islands are the driest region of the Lucayan Archipelago, with about 800 mm rainfall annually compared to 1200-1500 mm rainfall in the northern Bahamas , we consider it a possibility that the boas hide under these rocks for reasons of protection from predators, protection from overheating and optimal temperature regime and protection against water loss. Adults and juveniles are found in the same habitat type and micro-environments . This also refutes the possibility that the ontogenetic color change in this species is an adaptation for habitat change from juvenile to adults.

Buden implied C. chrysogaster is apparently abundant in the vicinity of Kew and can be found in and around settlements throughout most of the Caicos Bank. There are unconfirmed reports of its existence on East Caicos, Providenciales and Pine Cay . Per B. Naqqi Manco, “East Caicos definitely has Chilabothrus. Providenciales does too, we pretty regular get calls from people asking us to come take them away. Pine Cay – I’ve not known any from there. Parrot Cay definitely has them. We do a lot of fieldwork on Pine Cay”

B. N. Manco (pers. comm.) found the nominate subspecies in all habitats except mangrove. He reported to have most often found specimens in dry tropical forest with particularly large trees but also in pineyard, buttonwood swamp, oak bottoms, salt marsh, and even cactus scrub. Also often around buildings, houses and dumps. This is presumably because of the high density in prey/rats.

Historically speaking, the Caicos Bank appears to be shoaling. The West Indies Pilot (I: 84) states: There is no doubt that Caicos Bank will, in the course of time, become one island. All evidence points to its constant shoaling. Historical accounts of the pursuits of piratical craft across the bank by naval vessels in the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth century indicate that even 100 years ago deep channels existed where today a vessel drawing but six feet of water has to proceed with caution….

Longevity

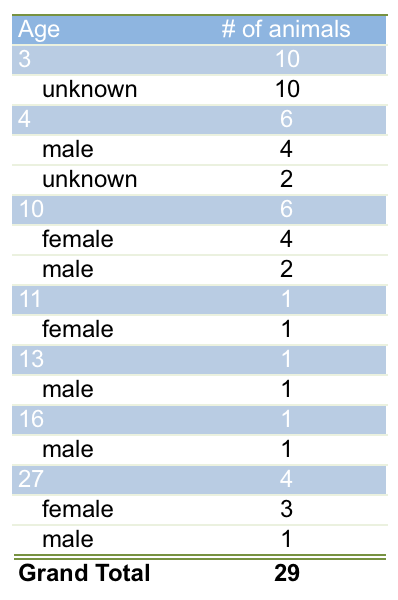

Currently (2020), several animals from the 1993 breeding of Joachim Bulian are still alive in collections, confirming an age of 27 years. The age distribution for captive specimens is shown in the table below. Snider & Bowler reported a wild caught male C. chrysogaster that had lived for 14 years and 2 month at the Houston Zoo, Texas .

Reproduction

Most of the knowledge we have about the reproduction of this species stems from captive breeding. The European private collectors have, historically, kept very good records of their breeding achievements with regard to the West Indian boas. Fortunately we have the following data to look back upon.

Bulian and Philippen described Bulians breeding success with Chilabothrus chrysogaster in two articles. His animals were bred in the collection of German breeder Hans-Dieter Lehmann on 12 September, 1984. Bulian obtained four siblings in 1986 and continued to raise them together. Matings were observed from 1.5.-25.5.1988. Matings lasted up to two hours and were observed every 2-4 days. Animals mated exclusively during daytime hours. Only the larger male mated and did so only with one of the females, even after removal of the mated female. While Bulian at his first breeding adjusted daylight hours to a shorter photoperiod, he later found out that breeding Chilabothrus chrysogaster did not depend on a photostimulus but relied on temperatures. Despite the success with his initial breeding strategy, Bulian in later years separated his animals during the the months February and March. He found that the animals mated upon reintrocution, which occurred beginning of April or beginning May (female into male terraria) immediately .

Contrary to this, J. Hohmann (pers. comm.), who also obtained a pair of animals from the Lehman breeding observed quite some differences in reproductive cycles. He kept his animals separated during the year and put them together around Christmas/Mid-End December. From the first day of keeping the animals together, he misted the cage and breedings occurred during the first quarter of the year. This is the coolest period of the year. The female would refuse to eat at one point and the mating would stop. This is when Hohmann separated the animals again. 6-9 young were born in September. He kept the animals quite cool during the winter with night time low temperatures frequently dropping below 20° C.

W. Bleuler (pers. comm.), having obtained a pair of animals from Hohmann through a middle man kept his pair of Turks and Caicos Boas together year round. His female gave birth to 6-9 young in the months September and October.

Buden notes that a wild caught gravid female collected on Caicos in June gave birth to 28 babies during 14-15 September . This number appears exceptionally large, however might be related to the age and size of the female. Bulian reported a female which had unfortuately died while gravid which contained 27 well developed young. The female was 8 years old. Bulian ascribed the death to the stress by the continued breeding attempts of the males and advocates separation of sexes after breeding .

A pair of boas maintained at the University of Michigan gave birth to nine babies on 27 February. Copulation took place on 5 June; gestation was 238 days long. Neonate weights were from 7.3 g to 8.4 g. Relative litter mass was 0.241 .

Some of the most recent breedings in the US are from the years 2010-2012 by Ryan Potts who imported several animals from Europe. He succeeded and obtained litters of six, seven and eight offspring in the years 2010, 2011 and 2012 from his breeding group. The young were born in September and October. Two more breedings occured in 2014 and 2015 when Tom Crutchfield obtained the breeding group from Ryan Potts.

Behavior

Chilabothrus chrysogaster is, like all members of the genus, an active nocturnal forager. It has been previously described as a rare example of a mainly terrestrial active forager , however, this view was challenged by an observarion of an incident where a Turks and Caicos Boa was found above the ground climbing was an observation by B Naqqi Manco who witnessed a rare climbing event in one adult individual on Pine Cay, Turks and Caicos Islands. The snake was displaying a stereotypical method of concertina locomotion often associated with other snake species, such as rat snakes (genus Pantherophis) and boa constrictors (Boa constrictor). This prompted the researchers to note that C. chrysogaster employs a similar strategy to climb like other snakes that are frequent climbers .

Reynolds and Gerber measured the body temperature (BT) and air temperature (AT) in wild C. chrysogaster on Big Ambergris Cay. They found a ratio of BT : AT of 1.03 on average. This shows the boas maintain body temperatures higher than air temperatures . The same study found a total of 249 Boas the vast majority was active at night during the time of the study (Beginning of December to Mid March). The authors conclude that the species is largely nocturnally active. The researchers found furthermore that C. chrysogaster is an active forager and not an ambush predator. While this study was extensive in its nature, there are still many open questions. E.g. do seasonal variations in nocturnal – diurnal activity patterns exist?

In terraria, the species seems calm several animals will regularly hide while others freely roam about. The boa will occasionally climb. We noted climbing behavior of both sexes particularly in the breeding season. They are especially active after sunset and feed more readily at this time. Some boas calm down with age while others remain skittish their entire life. One boa will not take food left in overnight or offered on forceps. The rodent must be rubbed on the snakes neck area until it throws a coil around the prey item; at this point it it can be left alone and eventually will eat the food item. Many baby Chilabothrus exhibit this behavior but soon grow out of it as they learn to recognize prey items. M. Saina noted that one of his animals, a female, showed a preference for hopper mice over larger mice. Several attempts of prey piracy were noted when feeding the animals in the same enclosure.

Diet

Diet of the nominate subspecies has been documented by several authors. Chilabothrus c. chrysogaster was observed to feed on small, introduced rodents such as rats and mice (Rattus, Mus), as well as eggs and birds (pigeon); as well as introduced birds such as chickens (Gallus). Saurophagy has been described in juveniles .

A video of a C. chrysogaster constricting an iguana can be viewed here.

Reynolds and Niemiller found a Chilabothrus chrysogaster on Gibbs Cay, a small island on the Turks Bank, consuming a Turks and Caicos Curly-tailed Lizard (Leiocephalus psammodromus). Since the island did not harbor populations of introduced rodents or chickens, the authors suggest that C. chrysogaster might be entirely saurophagous on small islands without Rattus, Mus, or Gallus .

Reynolds and Gerber found on Big Ambergris Cay, that C. chrysogaster was consuming lizards of four species (Cyclura carinata, Leiocephalus psammodromus, Anolis scriptus and Aristelliger hechti), as well as stalking a sleeping Spondylurus sloanii. They emphasize the idea that due to the lack of gallinaceous birds or rodents on many smaller islands it is probable that the majority of the diet of small island populations of this boa consists of lizards. Surprisingly, the authors of the study found several instances where C. c. chrysogaster was consuming carrion. Several adult road-killed Curly-Tailed Lizards, considerably degraded and dried out as well as a rotting road-killed carcass of a medium-sized female Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), to which the boas would come back on several nights and try to consume parts of it .

On Big Ambergris Cay, an adult female Turks and Caicos Boa was found to have consumed an introduced geckonid (Hemidactylus mabouia) . In addition to these observations, a picture series on Facebook showed an occasion where a C. chrysogaster on North Caicos consumed a large frog (possibly the introduced Cuban treefrog Osteopilus septentrionalis). This might possibly be the first instance where C. chrysogaster is reported to have consumed amphibian prey.

For breeders, the tiny neonates pose a challenge if no appropriate food items in the form of small anoles are available. Bulian who bred the species several times with good success up into the F2 generation used force feeding or assist feeding methods to feed the newborn with parts of newborn mice for a prolonged period of time . J. Murray raised his neonate and juvenile Turks and Caicos Boas using live anole prey which they took voluntarily and thrived on. Several youngsters fed on anoles for as long as 18 months.

Captive management and captive population

The species was imported several times and bred with success by private keepers as well as Zoos but without a structured approach of establishing a large captive breeding colony. Thus, the sentence from the 1972 price list of the San Francisco reptile dealer The Herpetarium: “Turk´s Island Boa Epicrates chrysogaster. Extremely rare. This species is conspicuously absent from every American and European zoo collection.” is valid until today.

This is surprising, since the species is easy to maintain once established and accustomed to their enclosure. Several factors seem worthy to mention. The species becomes accustomed well to their environment and the keeper. However, they seldom become as tame as Boa constrictor and continue to behave cautiously and retract quickly when the keeper comes close to the terrarium to observe them. In this respect, they are much different from Chilabothrus strigilatus. We noticed that animals show a high degree of individual preferences, especially when it comes to food items. Some animals take baby rats, while others prefer mice of a certain size only, other boas take every food item offered.

The biggest challenge to the keeper are newborn animals, since they require lizards (Anolis sp.) as food. Once switched to rodents, the animals are relatively easy to maintain. Bulian notes that while the rearing of young is laborious, it is possible without great difficulties .

Remarks: Baby Turks and Caicos boa from a captive breeding in 2011. This Animal is feeding on a brown Anole (Anolis sagrei). Anole lizards are the natural first food items for most West Indian Boas.

Babies, like several other species in the genus, are born red-orange and take 12-18 months to complete the ontogenetic color change.

A very small population is present in the private collections of American and European reptile keepers. We expect the current population to show a shallow genetic diversity, since to the best of our knowledge it was founded by very few animals and inbreeding between direct siblings occurs frequently. Currently, the genetics of the world captive population are being analyzed in a collaborative approach between hobbyists and academic researchers. The results will contribute to recommendations about steps necessary to secure species survival ex-situ.

Conservation status, threats and population size in nature

CITES: Appendix II

Bahamas joined CITES on 20 July, 1979; entry into force on 18 September, 1979.

IUCN Red List: None

Catalogue of Life: (click here)

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here)

CITES import/export data: (click here)

The recent rediscovery of this boa for the first time in the early 1970’s brought this boa back into the spotlight. It found its way into the commercial market and then on to the private collectors . CITES data for the period 1977-1983 showed but 2 specimens recorded as imports . It is “assumed” the remainder of the boas were illegally harvested during that time period.

The conservation status of the nominate subspecies varies among the different islands where it occurs. It had originally been described from Grand Turk, however, Buden noted that “the island of Grand Turk itself is now relatively well developed and well settled. None of the local residents I have talked to have ever seen a snake there. Residents of Grand Turk, however, report recent sightings of large snakes on some of the outer cays, particularly East Cay, which is located ca. 7.3 km southeast of Grand Turk”. He furthermore found the Caicos Bank “to show greater habitat diversity than those of the Turks Bank and have wooded areas as mesic as those of the more northerly islands in the Bahamas. The most luxuriant vegetation in the Caicos Islands is found in the northwest section of North Caicos and is centered around the settlement of Kew”, where he found C. chrysogaster most abundant. Interestingly, he found the boas to be relatively common on Little and Big Ambergis Cay – which were at the time uninhabited by humans .

Contrasting to this, 40 years later, the Big Ambergris Cay has human settlements and holds one of the most dense populations of Turks and Caicos Boas . The above observations made over time indicate that Chilabothrus chrysogaster might be able to co-exist in areas inhabited by humans; this is probably associated with the presence of a readily available food supply in the form of rats, mice, young chickens, and eggs. It would appear the population numbers are currently not a cause for concern right now; over three nights on Big Ambergris Cay, 37 C. chrysogaster were collected in 90 min, 47 in 100 min, and 56 in 110 min; only eight of those boas were recaptures (5.7%) (R.G. Reynolds, in litt., 6.viii.2019).

Introduced species are of particular concern especially on small islands. Several neozoa have been found on the Turks and Caicos islands, including cats (Felis catus), rats (Rattus rattus), Mice (Mus musculus) but also Reptile and Amphibian species, some of which are established on the islands . While the effects of rats and mice on C. chrysogaster are ambiguous (predator vs. food item), cats are a clear threat to the species due to predation and competition for prey species. The effects of introduced reptiles and amphibians are yet to be investigated and the observation that C. chrysogaster consumed a Cuban Treefrog might be considered as a positive sign of adaptability of C. chrysogaster in regards to its prey. Vehicle/road mortality is not yet taken into account as a threat and needs to be quantified to determine how this also affects the boa populations.

Human settlement and development are of great concern. Reynolds and Gerber noted that “Tourism increased nearly 90% between 1995 and 2005, and in the rush to accommodate these visitors, more than 20 resorts opened during the same period on the island of Providenciales alone. Incredibly, Providenciales has become so crowded in the last 15 years that new developments are moving to neighboring islands in the archipelago. In addition, small islands, such as Big Ambergris Cay, are being bought by foreign development companies and turned into exclusive vacation areas.” . Despite this, we see climate change as the biggest anthropogenic threat, since it will alter the habitats of C. chrysogaster in unprecedented ways over a very short time span.

Given the level and pace of development in support of the tourism industry and personal residences on the islands and cays, the future is indeed grim for these boas – and everywhere else in the Caribbean. As prey availability is affected and habitat loss increases, these boas appear extinction bound (see the study under C. fordii). When coupled with introduced feral animals that kill boas and compete for their prey resources and increasing numbers of natural disasters, scientists must complete their research projects while they can.

The shallow genetic diversity of the captive population, its age distribution, as well as the difficulty to reproduce the species successfully challenge the success for ex situ conservation. We would therefore praise any concerted approach that involves collaboration between in situ conservation and breeding programs, academic research and ex situ breeding programs. We are open for collaboration to any measure that ensures species survival in situ and ex situ. How long can these beautiful and wonderfully unique boas continue their tenuous grasp on life in the West Indies?

We consider both subspecies prime candidates for the Invisible Ark.

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for The Turks and Caicos Islands: limited natural freshwater resources, private cisterns collect rainwater .

The maps below illustrate the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture.

On display in these Zoos

Currently we are unaware of any live Chilabothrus chrysogaster in Zoo or academic collections anywhere in the world. If you have further information, please notify us.

Tantalizing Turks